When COVID-19 dismantled global institutions and economies, its impact went wide and deep, leaving people, families and communities in a swirl of distress and deprivation.

In India, the nationwide lockdown to contain the contagion restricted more than a billion people to the confines of their homes. On the other hand, it left several millions stuck away from theirs — a thousand miles away.

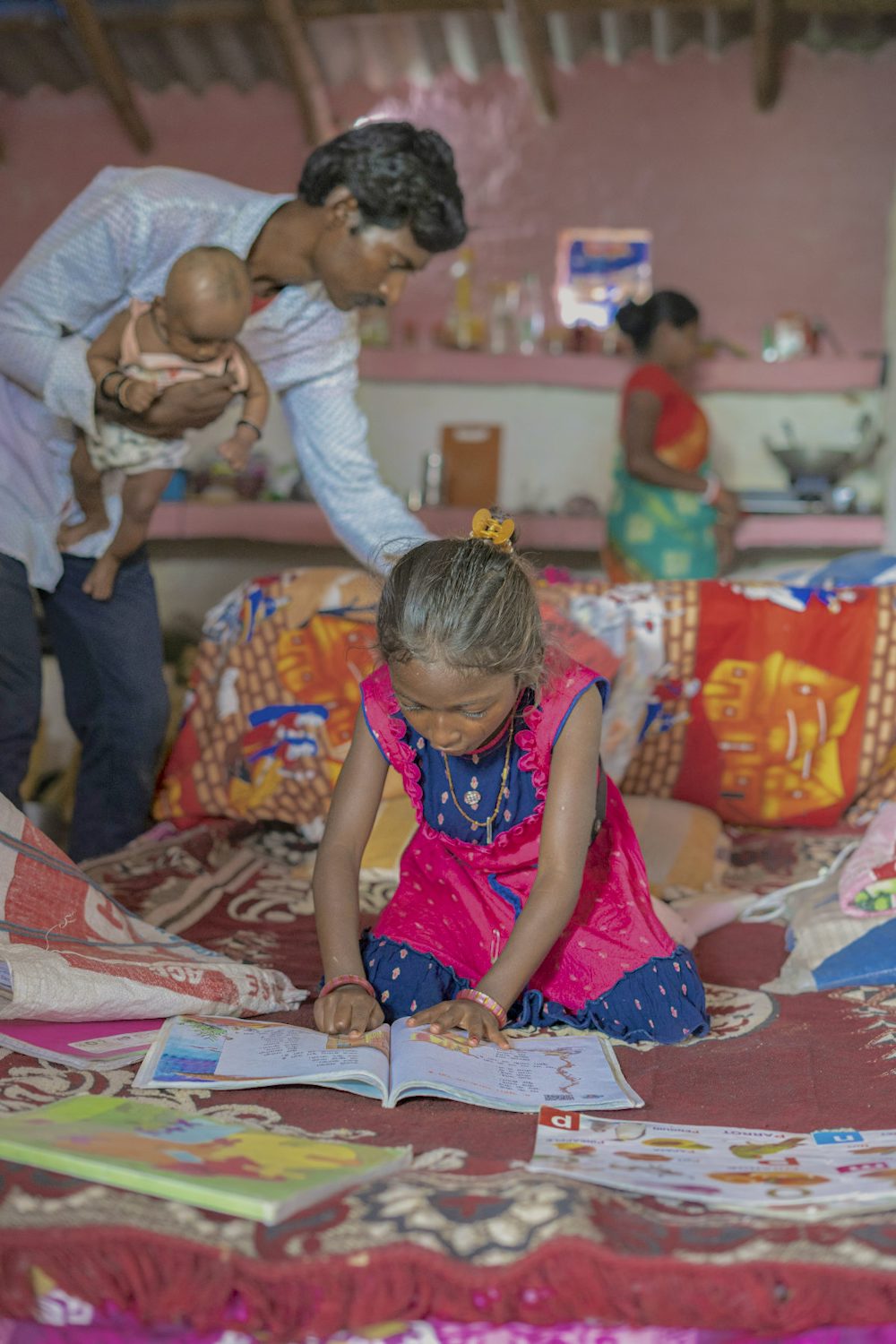

Montu Naik and his family were some of them.

More than 100 million migrant workers live in India’s cities, a majority of those who, like Montu’s family, have migrated from rural areas in search of employment opportunities. Migrant workers like these are often forced to work in the informal sector as daily wage laborers — working at construction sites, pulling rikshaws, working as vegetable vendors — to support their families.

To sustain themselves and save enough, they live under hazardous conditions: in congested rooms of crumbling housing, with inadequate water and electricity, lack of sanitation and limited access to health facilities. Often prone to discrimination and exploitation, they also are more vulnerable to losing their livelihood in the face of unrest and calamities — such as COVID-19.

Despite the injustice migrant workers face, it’s often the only opportunity people have to overcome the rampant poverty of rural areas.

“My parents moved to Delhi in 1984 in search of work,” Montu shared, explaining his family’s migration from their home village of Budara, in India’s Odisha state, and the plight of hundreds of thousands of migrant workers like them. "They did odd jobs, worked as a daily wage laborers.”

Though they returned to visit their extended family in Budara as often as possible, the dearth of job opportunities there made it impossible to stay. When Montu had a family of his own, he felt his best chance at supporting them was to try to make ends meet in Delhi, too.

“I used to work as an assistant at a convenience store, selling groceries and other items,” Montu shared. “I was working day and night shifts and earning around 13,000 India Rupees [$170] in a month.”

When the pandemic struck, Montu was at the edge of losing his job — the job that paid for his house in the city, put food on his family’s table and paid for the education of his daughter, Sagarika.

Many migrant workers were left in the same predicament — and mass layoffs left millions out of work. Having lost their livelihoods, left with negligible savings and an uncertain future ahead, approximately 10 million migrants were forced to defy state orders and travel back to their hometowns by whatever means they could find — bus, train or by foot — to survive.

While Montu was able to retain his job, it didn’t feel sustainable. “During that time, I would do extra hours despite the salary cuts,” Montu shared, referring to the deteriorating conditions around him. “I realized that it’s going to be difficult in future and I must do something.”

After navigating the pandemic for a year, Montu and his family decided to return to their village in January 2021 with mixed sentiments — relief of coming back to their people and fear of an unpredictable future.

Heifer operates its Hatching Hope India initiative in villages throughout Odisha and, after his arrival in Budara, Montu attended one of the awareness sessions on starting a poultry business hosted by the project team.

The project, a collaboration of Heifer and Cargill, promotes poultry production as a means to improve nutrition and income in communities like Montu’s. Through training and awareness campaigns, it helps communities learn the foundation of poultry production and the benefits of nutrition from poultry products.

“When I heard about it, I was reluctant,” Montu shared. “But when I attended the session, I felt a lot [more] confident. I felt positive about starting my small business in my own village.”

Diving deeper into his training, Montu continued to learn from a mobile application designed to train farmers around poultry production practices.

“I learned about how to keep chicks, how medicines are important for them to protect them from diseases, and that we need to feed them well,” he shared.

Intrigued by the prospects — and trained by the project — Montu took a leap and started a poultry farm.

“I am already earning more than 15,000 rupees a month,” he said, reflecting on the increased income — nearly 20% more — he is earning as a poultry farmer over a migrant worker.

To run his farm, Montu often travels to nearby markets to get feed and farming equipment. Meanwhile, his wife Janki supports him in taking care of the farm. “I make sure that the farm is clean,” she shared. “Maintaining the farm is my responsibility. I like this poultry business. It gives us better income."

Back in their village, Montu and Janki have expanded their farm to cultivate vegetables in their kitchen garden. “Our nutrition has got better,” Janki shared. “We grow our food ourselves here without pesticides — the quality is different.”

And with his thriving poultry business and aspirations to scale it beyond a thousand birds, Montu has his sights set on a future — at home.

“If you want to stay back in your village, you can start small and earn through it,” Montu shared. “You don’t always have to move. ... Opportunities exist here also.”