This Juneteenth, we recognize that supporting Black food producers is timeless and overdue.

Every day you take a bite of Black history, whether you’re patronizing Black-owned restaurants — as recent events have inspired many to do — or just serving food on your table at home. From enslaved people who brought black-eyed peas to our soil to the rice cultivation techniques used in the colonial South, the seeds of Black people's contributions were planted long before they could legally and rightfully reap the benefits.

The upcoming Juneteenth holiday, celebrated annually on June 19, serves as a reminder of the enslavement and long-awaited freedom of Black Americans. It marks the day that Union General Gordon Granger proclaimed freedom from slavery in Texas in 1865 — two years after the Emancipation Proclamation officially freed enslaved people living in the rebellious states in America. This day and other fleeting periods of the year — Black History Month and Martin Luther King Day — push the past to the present, encouraging introspection on the country’s progress in regard to race relations and the advancement of Black people in this country, only for the buzz to quiet down the rest of the year.

The Power of Collective Action

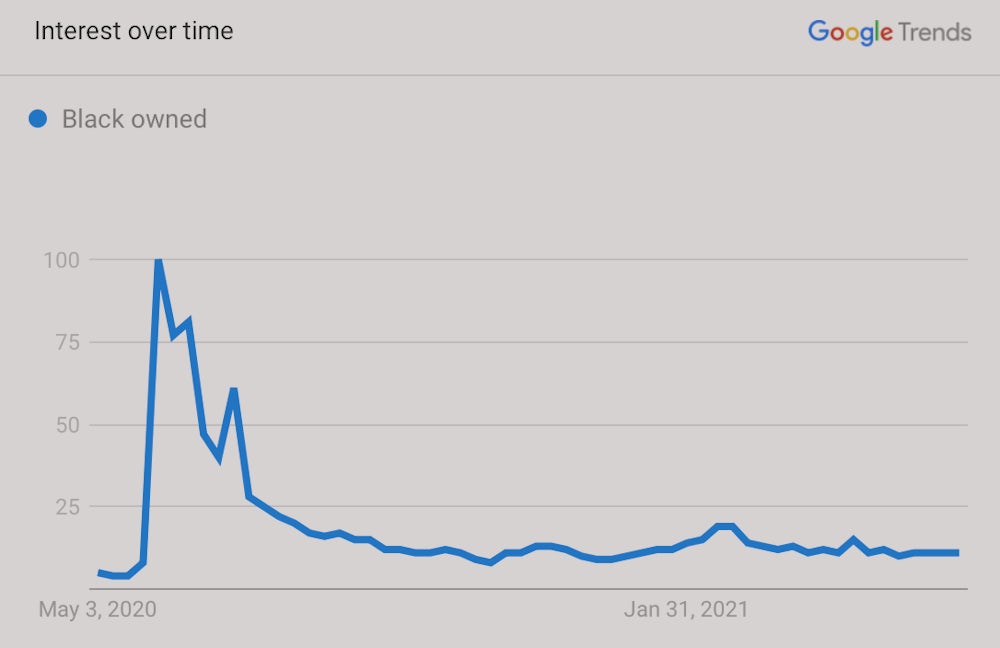

After protests in 2020 awoke calls for racial justice and equity, interest in Black-owned businesses and Black-developed products surged. Google Trends show that interest in the search term “Black owned” had a value of 8 from May 24-27, 2020, and rose to 100 the following week. Now, a little more than a year later, it has fallen to a value of 10. This rise in interest in “Black owned” products and businesses, acts of diversifying companies and removing Black faces from non-Black-owned food products may seem to be milestones of progress, but if the momentum is to be sustained, there needs to be continued acknowledgement of Black people's contributions to our society, as well as the historical challenges they’ve faced. Without this, acts to establish an equitable society, let alone food and farming system, may never be realized.

Sowing Seeds of Progress

Research in Judith Carney’s “The African Origins of Carolina Rice” highlights “the role of Africans and African women in introducing an important agricultural system that forever changed the food culture of the Americas.” The wetland rice system that appeared in South Carolina during the earlier colonial period most likely originated in West Africa, as she states, “only West African slaves knew the wet rice farming system,” while the farming system that the English and French practiced when they emigrated relied on growing crops by rainfall.

African women, Carney notes, were heavily involved in growing rice during the Atlantic slave trade, with their knowledge proving critical to its cultivation in the Americas. During the colonial period, rice was processed using a mortar and pestle, a method used to process cereals and root crops in Africa, where women had the responsibility of hand-milling rice. This proved to be valuable as the rise in popularity of rice in South Carolina not only relied on the ability of people to cultivate it in wetlands, but its value as an export crop also depended on “the knowledge of how to process and mill rice for international markets,” a point Carney makes citing a report by Edward Randolph to the Council of Trade and Plantations in 1700.

Foods with African roots such as watermelon and cooking styles such as barbecue have crossed the ocean and are now enjoyed by people of all ethnic and racial groups. The visibility of Black people in America’s food and farming spaces seems to be increasing with time, but their equity in the space and profits haven’t always reflected that. Last September, The Coca-Cola company’s Chief Customer Officer Kathleen Ciaramello reported that a survey it commissioned showed that 35% of consumers expressed they are more likely to search for and visit Black-owned restaurants, and “the percentage is even higher among urban and younger consumers.”

Black People in America's Food and Farming Spaces

While lists of Black-owned restaurants and Black food experts inundated the internet last year, the reality is Black people already existed in these spaces and other parts of the food industry, be it not in great numbers. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2020, those who identified as Black or African American farmers, ranchers and other agricultural managers made up 0.7% of the total population. Representation in the culinary space showed almost 15% of the total population identified as Black or African American chefs and head cooks. With more organizations voicing their commitment to diversity and new funding opportunities, there is hope, but these efforts must continually be evaluated to determine their effectiveness. Even with good intentions, some support has been misrepresented, fallen short of its goals or been challenged.

According to the USDA’S 2017 Census of Agriculture, Black-operated farms accounted for 4.7 million acres of farmland, 0.5% of the U.S. total, and sold $1.4 billion in agricultural products, accounting for 0.4% of total U.S. agriculture sales in 2017. These recently reported small percentages of land and sales, coupled with the fact that Black farmers lost approximately 90% of their land between 1910 and 1997, make it clear there needs to be systemic change that will lead to positive and sustainable results.

Some Black actors in the country’s food and farming sectors have had deep conversations with Heifer International’s CEO and President, Pierre Ferrari, and other senior leaders, expressing what they consider genuine support. During one of these conversations, Foot Print Farms CEO Cindy Ayers Elliott said, “I don't want the 40 acres and a mule, I want the 40 acres and a John Deere” — referencing the long and bitter history of broken promises caused by systemic issues including government policies that have disenfranchised Black Americans. Despite the hard work of restitution champions like General William Sherman and General Oliver Otis Howard, who tried and failed to protect restitution acts and land rights of freed enslaved people in the late 19th century, there has never been tangible compensation for enslaved people or their descendants for their contributions during slavery.

The Economic Benefit of Equity

Continued support of Black people in America will not only create a more equitable society, but a space where everyone can thrive. McKinsey & Company says, “An investment in more business ecosystems that provide Black business owners equitable access to resources and opportunities can unlock part of the $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion in annual GDP that would come from closing the racial wealth gap.”

This is a future goal we can all invest in! Despite the historical and present-day challenges Black people in America face in the food and farming spaces, their participation has yielded, and continues to yield, food that everyone can appreciate. To engage and show continued support of Black people in America’s food sector, check out: