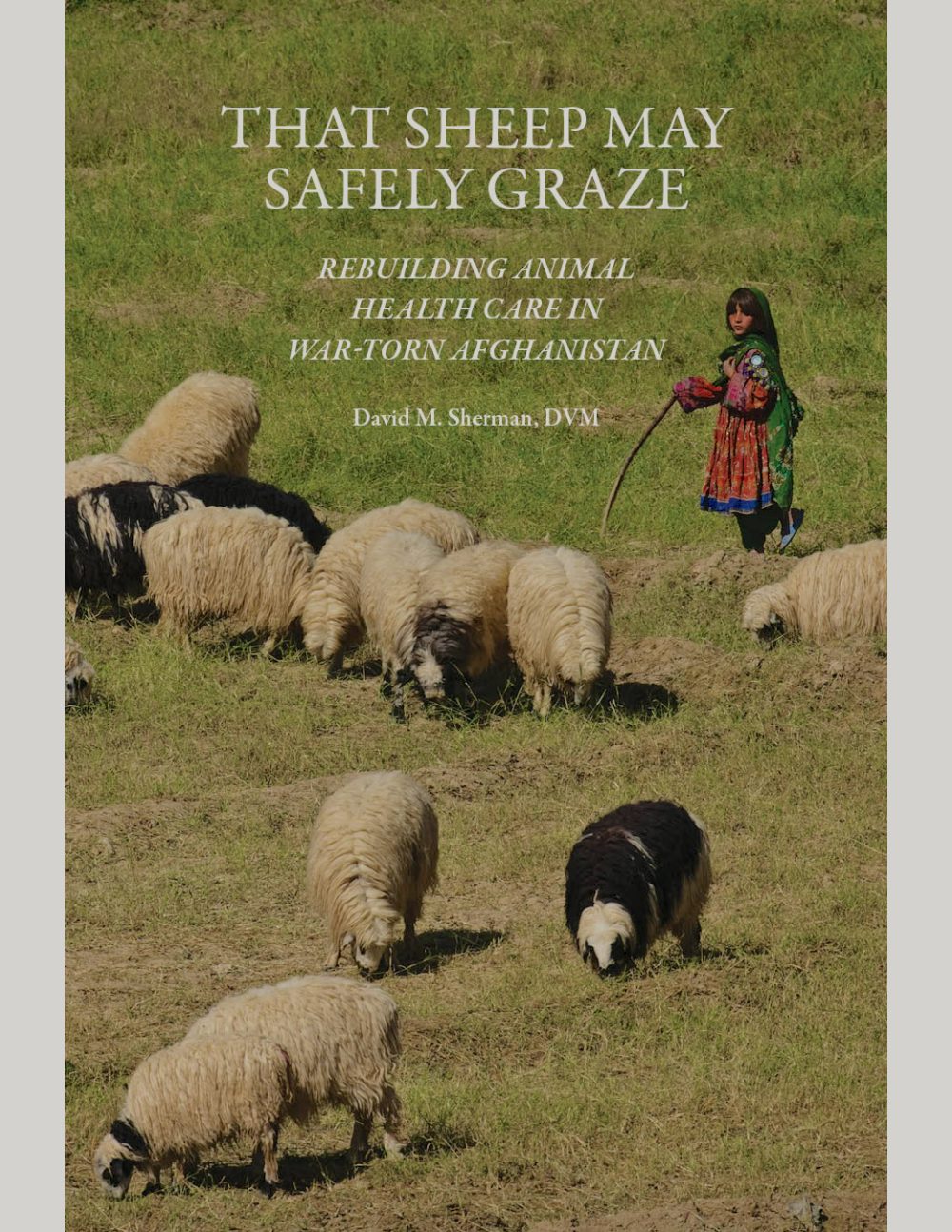

How can farmers keep their flocks healthy when war and hardship put livestock at risk? Veterinarian David Sherman is an expert at devising systems and solutions to care for animals in war-torn regions. In his book That Sheep May Safely Graze, Sherman offers up a roadmap for how to deliver community services in unstable countries. He also makes the case for helping at-risk nations proactively to stave off war, rather than waiting to offer aid in the aftermath of violence and destruction.

Can you describe how and why you became involved in animal health care in developing nations?

As a veterinary student, I originally planned to do dairy practice somewhere in rural America. But during an internship in large animal medicine at the University of Minnesota, in addition to the cattle I expected to see, I encountered quite a few goats being brought to the veterinary teaching hospital in St. Paul. I took an interest in them and used my internship to learn as much as I could. I went regularly to the library to read up on the cases I was seeing and quickly realized that veterinary textbooks had very little specific or reliable information about diseases of goats. It was often presumed by the authors that goat maladies and their treatments were the same as for cattle or sheep. My experience was telling me that often this was not the case, so I developed a professional interest in expanding veterinary knowledge about goats. This led to the opportunity to co-author the first definitive veterinary textbook dedicated solely to the diseases of goats, Goat Medicine.

There was considerable international interest in Goat Medicine, as the vast majority of the world’s goats are located outside of North America. As a result, I began to receive requests from non-governmental organizations and international agencies to consult abroad on goat health and production issues, mainly in Africa and Asia. During these visits abroad, I learned some important lessons. Goats were often owned by the poorest people in rural settings and their goats were often their most valuable asset. So, keeping them healthy was critically important. The death of their goats could mean the loss of their livelihood. At the same time, it became apparent to me that poor, rural livestock owners in developing countries very often had little or no access to veterinary care. As a result, preventable or easily treated animal diseases resulted in death. During a mission in Bangladesh, I met a poor, distraught widow in a rural village who had just lost four out of five of her goats to a disease that was easily preventable by a vaccine that cost just pennies a dose, but which was not available to her. I was deeply moved by this encounter and decided to turn my professional interest to ‘last mile’ veterinary service delivery, working to ensure that basic animal health care services are reliably available in poor rural areas. The work I did in Afghanistan on veterinary service delivery, as described in That Sheep May Safely Graze, traces back to my meeting with this unfortunate widow.

In what countries have you worked?

The first international development work I did was for Heifer International, consulting on goat projects in Taiwan and the Sichuan province of China. Since then, I have lived in Pakistan for two years and in Afghanistan for five, in both cases working on community-based animal health care delivery. I have also worked in Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Uganda in Africa, Bangladesh and Mongolia in Asia and Jordan in the Middle East. More recently, working for the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), I visited Laos, the Philippines, Vietnam, Nigeria, Sudan, Zambia, Turkey, Israel and Panama to help strengthen their national veterinary services.

Why did you write “That Sheep May Safely Graze”? Who should read it?

My main motivation was to share the story of a successful development project in Afghanistan that continues to provide tangible, long-term benefits for Afghans 15 years after its conception. It is no secret that the American adventure in Afghanistan since 2001 has come up short. The Washington Post ran a week-long exposé in December 2019 that characterized the 18-year nation-building effort in Afghanistan as a failure mired in arrogance, ignorance, incompetence, waste, corruption and deceit, with many Afghan and American lives lost, hundreds of billions of dollars spent and very little of lasting value to show for it. The animal health care project described in the book is a notable exception that deserves recognition. The Washington Post revelations came as no surprise to me. Working on this project in Afghanistan from 2004 to 2009, my colleagues and I encountered firsthand all of the negative factors enumerated by the Washington Post. Yet we were able to work around all of these challenges and produce something beneficial and lasting for the good of the Afghan people. I believe it is worth detailing the reasons that this project was a success so that future efforts at nation-building can be more successful. People disillusioned with the record of America’s involvement in Afghanistan should at least know of our successful effort to provide sustainable animal health care in a country heavily dependent on animal agriculture and be encouraged that indeed, effective development in Afghanistan is possible.

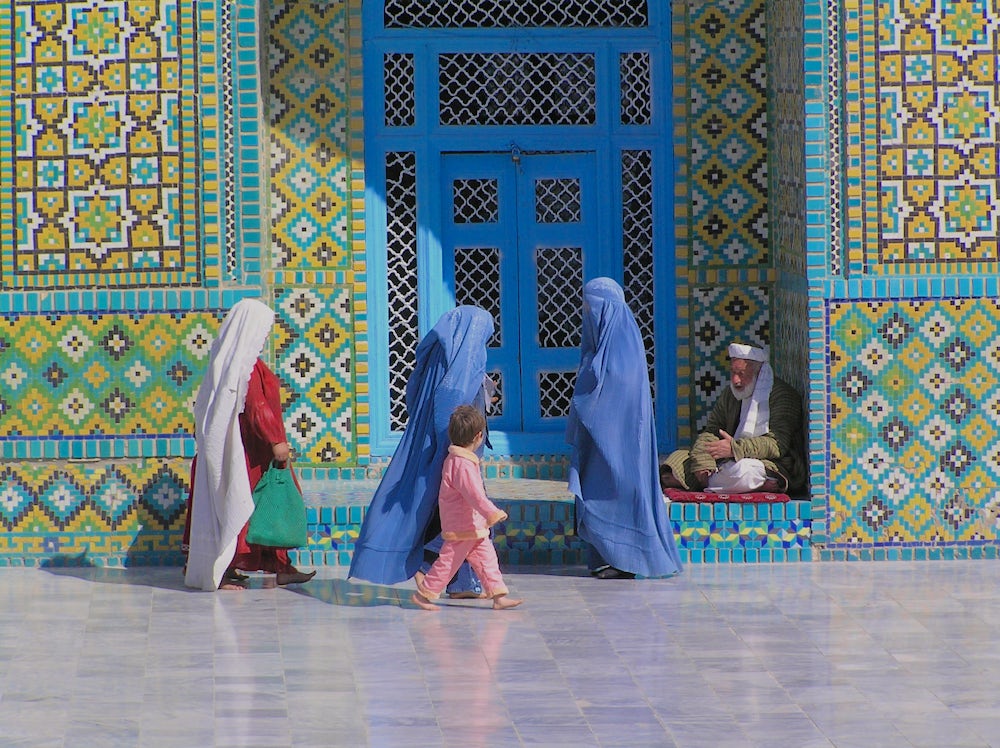

Who should read this book? Anyone who has been curious about or had a connection to Afghanistan should find this book informative and interesting, including soldiers and their families, development practitioners, aid workers, government employees, politicians and policymakers. Educators and students studying international development may also find this a useful case study for discussion. Veterinarians, veterinary technicians, livestock keepers, animal lovers and supporters of Heifer International who understand the importance of livestock for the wellbeing of rural people in developing countries should also find it engaging.I also had a personal reason. My work with Afghans and Afghanistan first began in 1991, so I have a long relationship with the country and have made lasting friendships there. I wanted to invite readers to get to know some of the fine and decent Afghans with whom I worked, so that they can better appreciate the warmth, grace, humor and resilience of these people in the face of the tremendous hardships and losses they have suffered for decades.

We often hear about new technologies and cutting-edge approaches to end global poverty. Livestock is a decidedly non-glamorous solution. Do you ever feel like your work is undervalued?

When animals and their offspring thrive and produce more than can be consumed by the families who own them, opportunities for commerce emerge. When this happens, farmers, processors, transporters, wholesalers, retailers, consumers and the overall economy all benefit. It is certainly not undervalued by the people who benefit from it, but I take your point. The fascination with bells and whistles aside, the fact remains that in much of the developing world there are hundreds of millions of livestock keepers living in countries where agriculture is the main economic activity and livestock production contributes to that agricultural economy. Often, however, the full value of livestock goes unrealized because of multiple constraints on animal production, processing and marketing. To develop that potential, step one is to keep animals alive and healthy and make them more productive. This means improving their nutrition and genetics and keeping disease at bay. Disease control is the highest priority, as the gains realized through better feeding and genetic improvement can be quickly lost if highly contagious diseases cause deaths or keep animals from reproducing.

What were the biggest obstacles you faced setting up the paravet network in Afghanistan?

Many people I speak with assume that the biggest obstacle to our work was the fact that we were operating in a war zone. In fact, despite the occasional anxious moment, that had very little effect on our work. The lack of infrastructure, particularly the lack of electricity, was a challenge since we had to ensure that our vaccines remained refrigerated. We addressed this problem with solar-powered refrigerators.

Our biggest obstacle was resistance from the government. They were incensed that our donor, USAID, chose to fund an NGO to develop a private sector veterinary services network operated by veterinary paraprofessionals rather than providing funds to rehabilitate the network of provincial government veterinary clinics that existed before the Russian invasion in 1979. The degree of hostility was such that at one point, the chief veterinary officer of Afghanistan tried to have me removed from the country and have the project closed down, as described in the book.

Another surprising obstacle was resistance from some other NGOs. The key to sustainability for our project was to have farmers and herders pay for the goods and services they received so that the paravets would have a regular income to resupply their stocks and continue to provide service long after our project ended. Yet some other NGOs insisted on providing medicines and vaccines for free, sometimes in the very same districts where our paravets were working, thus undermining our sustainability. Because if the service was free and the cost is underwritten by a donor-funded project, then when the project ended, so did the service and the access to medicines and vaccines. Under our fee-for-service system, we expected that veterinary services would continue long after the project ended. And in fact, the vast majority of the paravets we trained since 2004 are still actively working in the private sector, some now for as long as 15 years.

What are some of your favorite slices of Afghan culture?

A memorable aspect of Afghan life for me was the Afghans’ love of picnics. This was a major recreational activity on weekends when families, or groups of male friends, would travel out of the city, set out carpets under the trees, build a charcoal fire and prepare a feast of lamb or beef kebabs with Naan bread, followed by apples and oranges and strong, sweet tea while enjoying their natural surroundings. Afghan food in general was excellent and meals taken in the homes of Afghan hosts were always impressive for their variety, deliciousness and abundance. If there happens to be an Afghan restaurant in your community and you have never patronized it, I would encourage you to check it out.I never ceased to be amazed and gratified by the dignity, generosity and hospitality of the Afghans I worked with. After 30 years of invasion, war, suffering and loss, I would have understood if Afghans projected grievance, bitterness and depression. If these emotions were present in my colleagues, they were well hidden because their interactions with me were characterized by warmth, good humor and camaraderie. I presume that for many, this was a function of their strong Islamic faith, as evidenced by their observance of afternoon prayers at the office every day.

While Afghanistan continues to struggle on many fronts, your work building an infrastructure for animal care there was largely successful. Why is that? What lessons can you share for successful development work in politically charged regions?

The reasons Afghanistan remains on the brink of being a failed state are numerous. Yet in the face of all this dysfunction, we were able to accomplish something useful and lasting. How so? First of all, we worked on something that the Afghans themselves identified as a real need. Surveys of livestock owners conducted after 2001 identified lack of access to water and lack of access to veterinary care as the two main constraints on their livestock activities. As we were not water engineers, we focused on animal health care delivery. Second, a group called the Dutch Committee for Afghanistan had been working in the country since 1988, focused on the livestock sector and already training paravets when this new project began in 2004. Third, we adopted a community-based approach and engaged Afghans as stakeholders. It was community leaders and livestock keepers who selected the young men and later, women, to be trained as paravets, and they committed to paying for the services that the paravets provided. Fourth, we took a holistic approach to project development, ensuring that all the elements necessary for success were fully addressed. In that context, we refined and delivered a six-month training curriculum, procured high-quality medicines and vaccines, developed a solar-powered system to keep vaccines refrigerated, educated farmers about paravets’ services and monitored the quality of care the paravets delivered. Perhaps most importantly, we set an exit strategy into our project right from the beginning. By not paying salaries to paravets, by insisting that communities pay for services, by ensuring the quality of goods and services provided so that livestock owners would be satisfied and continue to pay, and by establishing a private company run by Afghan veterinarians to continue to procure high-quality vaccines and medicines, we ensured that the paravets could continue to provide services to their communities long after the project ended.

All photos and captions by David Sherman.

Learn more about David Sherman's ground-breaking work in Afghanistan in his book Where Sheep May Safely Graze. You can purchase a copy from the Purdue University Press or from Amazon.com.